تمنع السلطات اللبنانية سكان المخيمات الفلسطينية من إدخال مواد البناء منذ 25 عاماً. فلا يمكن البناء فيها، إلا باستثناءات نادرة جداً. لكن هذه ليست المشكلة الوحيدة. فبحسب تقديرات الأونروا، نحو 5500 منزل في هذه المخيمات بحاجة إلى ترميم، ما يهدد حياة آلاف السكان، نظراً لاحتمال انهيار أجزاء منها.

جمعت «أخبار الساحة» شهادات لعدد من اللاجئات/ين، يتحدثون فيها عن ظروف سكنهم السيئة والمقلقة.

شهادة 1 | مخيم البص

أعيش مع طفلي، بعد أن انفصلت عن زوجي، في منزل قديم في الطابق الثالث، بدأت التصدعات تظهر في جدرانه. خفت وبدأت بالاقتراض من أهلي وجيراني كي أرمم المنزل.

تقدّمت بطلب ترميم عبر المهندس المسؤول عن المخيم، لكن الطلب رفض. ثم لجأت إلى الأونروا، فأخبروني أنه «عليّ انتظار الدور». الدور الذي أعطوني إياه كان بعيداً جداً، ولا يمكنني البقاء مع طفلي في منزل قد ينهار في أي لحظة.

تواصل أخي مع تاجر يبيع مواد البناء بشكل مهرّب ضمن المخيم، ثم بدأنا الترميم، وبعدها بأسبوع جاءت دورية إلى المنزل وقبضوا عليّ. بقيت في الحجز ثلاثة أيام، بينما هدموا ما عمّرته.

خرجت من الحجز وانتقلت مع طفلي للعيش في منزل أختي في مخيم المية ومية، الذي يتألف من غرفتين وصالون.

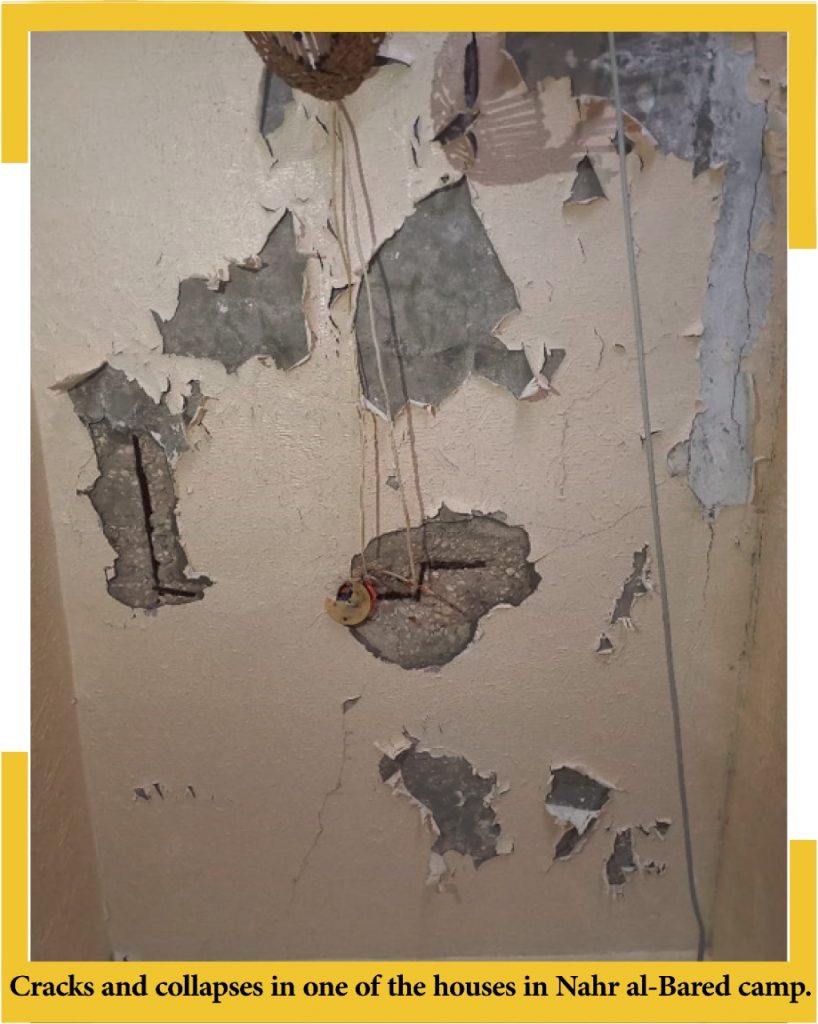

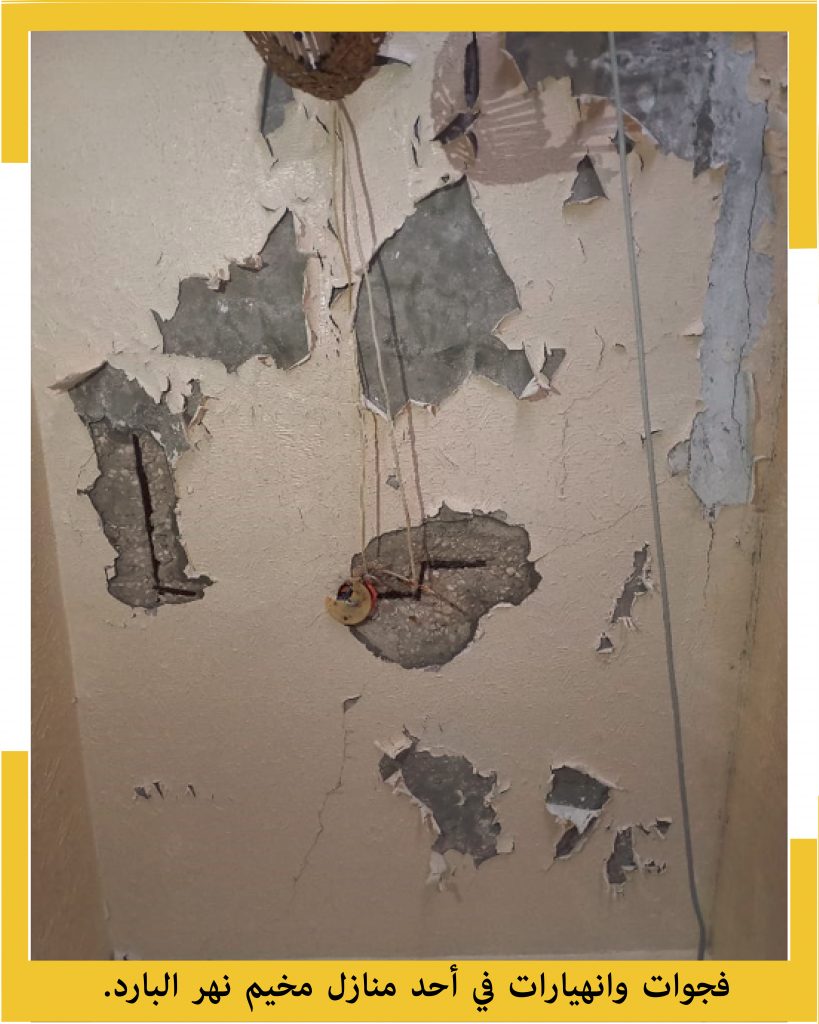

شهادة 2 | مخيم نهر البارد

كنت أعيش مع ابنتي في مخيم نهر البارد، في منزل مؤلف من غرفتين وصالون في الطابق الثاني.

بدأت مشاكله بالظهور منذ تسع سنوات، مع تسرب المياه في الحمام. كلما تساقطت الأمطار، يبدأ السقف بدلف المياه فيه، وقد تعرّضنا للصعق بالكهرباء أكثر من مرة.

حينها، تقدمت بطلب ترميم للأونروا. أول مرّة، عبر اللجنة في المخيم، فأعطوني ورقة صغيرة عليها رقم وطلبوا مني المراجعة بعد عام. وعندما راجعتها، قيل لي «لا يوجد لدينا ملف باسمك».

قدمت طلباً آخر، وعاودت الانتظار. طيلة السنوات السبع كنت أراجع الوكالة كل عام، ولا ردّ إلّا التأجيل.

في السنة الأخيرة، انهار جزء من السقف فوق رؤوسنا، فغادرت المنزل مع ابنتي والقليل من أمتعتنا إلى منزل ابني في صيدا، خارج المخيم، ثم راجعت الأونروا وطلبت إرسال لجنة للكشف على المنزل، والإسراع في ترميمه.

أخبروني أنهم لا يستطيعون الترميم طالما أنني أسكن خارج المنزل، وخارج المخيم. قالوا لي «عليكِ العودة إلى المنزل كي نستطيع ترميمه». لكن كيف لي أن أسكن في منزل تنهار أجزاء من سقفه، جدرانه متصدعة، وتسرب المياه فيه يؤدي إلى صعقنا من كل مقبس نلمسه؟

شهادة 3 | برج البراجنة

خلال الاجتياح الإسرائيلي عام 1982، تهدّم حمام منزلنا المصنوع أصلاً من «الزينكو». غادرناه لفترة على أمل ترميمه، لكن من دون جدوى. ففي كل مراجعة للأونروا، يخبروننا أن «كل بيوت الزينكو سوف تهدم، وتبنى من جديد قريباً»، فعدنا إليه على حاله.

لمدة ست سنوات، ونحن نستخدم حمّاماً خارجياً بجانب المنزل، مغطى أيضاً «بالزينكو». ومع أول سقوط للأمطار هذا العام انهار جزء من سقف الصالون، ثم تصدّعت جدران الغرفة الأخرى. راجعت الأونروا وطلبت إرسال لجنة للكشف، فأرسلت لجنة تسجيل الأضرار، لكن الترميم لم يحدث حتى اليوم.

ممنوع علينا الترميم وحدنا. أصلاً، لا يسمح بإدخال مواد البناء إلّا عبر الأونروا. وفي حال حاولنا الترميم، فإن تكلفة مواد البناء مرتفعة جداً ولا يمكننا تحمّلها، عدا عن أن ذلك يعرّضنا للحجز لدى مخابرات الجيش.

لم يعد لدينا حل. غادرت المنزل مع عائلتي، واستأجرنا منزلاً ضمن المخيم.

شهادة 4 | عين الحلوة

أعيش مع زوجي في هذا المنزل منذ أكثر من عشر سنوات، وكان وضعه مقبولاً، مقارنة ببيوت المخيم الأخرى. منذ سبع سنوات، وأثناء تشييع، اخترقت رصاصة جدار الغرفة، وأخرى سقف المطبخ. ومع أول شتاء، بدأ تسرب المياه ومعه ظهرت التصدّعات.

تقدمنا بطلب ترميم للأونروا في السنة نفسها. طُلب منا الانتظار والمراجعة بعد عام. في العام التالي، أُبلغنا برفض الطلب، من دون إيضاح الأسباب.

في كل عام، نعيد تقديم الطلب، من دون تغيير يذكر. قد ينهار المنزل فوقنا. أعيش مع هذا الخوف في كل لحظة، لكننا لا نستطيع المغادرة. فلا أقارب لنا يستطيعون استضافتنا عندهم، ولا قدرة لنا على استئجار منزل، وكل ما أملكه هو الأمل بأن «يحنّوا علينا».

ملحق

يشكو ناشطون تواصلت معهم «أخبار الساحة»، أن طلبات الترميم المقدّمة عبر الأونروا تأخذ وقتاً طويلاً للبتّ بها، وهنالك دائماً محسوبيات لمصلحة الفصائل المسلحة. وهذا التمييز لا يقتصر على عمليات الترميم الملحة، التي تُرفض طلباتها في الغالب، بل ينسحب إلى بناء منازل أو عمارات جديدة أيضاً.

ويقول ناشط في مخيم البرج الشمالي، إن حركة فتح عمّرت في العام الماضي مبنى مؤلفاً من 3 طوابق بتصريح رسميّ، حصلت عليه عبر دفع رشوة لضابط في الجيش، وفق ما يتناقل سكان المخيم. بالطريقة نفسها، بحسبه، تحصل الفصائل على أذونات لترميم المنازل التابعة لها، من دون أي اهتمام ببيوت المدنيين التي تتساقط فوق رؤوس أصحابها.

Discrimination against Palestinian refugees threatens their homes with collapse

The Lebanese authorities prevent the residents of Palestinian camps from bringing in construction materials for 25 years now. It is impossible to construct within the camps, except for very rare exceptions. However, this is not the only issue. According to the estimates of the UNRWA, around 5,500 houses in these camps need to be repaired, the thing that threatens the lives of thousands of residents, due to the possibility of collapse of some parts of them.

“Akhbar Al-Saha” collected testimonies from a number of refugees, where they talked about their poor and alarming living conditions.

Testimony 1 | Al Bass camp

After I got separated from my husband, I started living with my child in an old 3rd floor apartment, where cracks started to appear on the walls. I got scared and started borrowing money from my family and neighbours to renovate the house. I submitted an application for renovation through the engineer in charge of the camp, but my request was rejected. I then turned to UNRWA, and they told me, “I have to wait for my turn.” The turn they gave me was very distant in time, and I cannot stay with my child in a house that might fall down at any moment.

My brother contacted a trader that sells smuggled construction materials among the camp, and we started repairing the house. About a week later a patrol came in and arrested me. I stayed in confinement for three days, while they demolished what I had built.

When I was released, I moved with my child into my sister’s house in “Mieh w Mieh” camp, which consists of two rooms and a living room.

Testimony 2 | Nahr al-Bared camp

I used to live with my daughter in Nahr al-Bared camp, in a two-roomed house and a living room on the second floor. The problems in the house began to appear nine years ago, with water leaking into the bathroom. Whenever it rains, the roof starts to leak water, and we have been prone to electrocution more than once.

At that time, I submitted an application for house restoration at the UNRWA. The first time, through the committee in the camp. They gave me a small piece of paper with a number on it and asked me to come check in a year. And when I did, I was told, “We don’t have your name in any file.”

I submitted another one and waited again. I reviewed the agency on a yearly basis throughout the past seven years, and they never had a response other than postponement.

Last year, part of the ceiling collapsed over our heads, so I left the house and parted with my daughter and few of our belongings to my son’s residence in Saida, outside the camp. Then I went to UNRWA and asked them to send a committee to inspect the house and hasten its restoration.

They told me they can’t repair the house as long as I reside outside it, and outside the camp. They said, “You have to go back to your home so we can fix it.” But how can I live in a house where parts of its roof are collapsing, where walls are cracked, and where the water leakage is electrocuting us every time we touch a socket?

Testimony 3 | Bourj Al Barajneh camp

During the Israeli invasion in 1982, the bathroom of our house, which was originally made from “zinco”, was demolished. We left it for a while hoping to later restore it, but to no avail. In every visit to UNRWA, they tell us that “all the houses made from zinco will be demolished and rebuilt soon,” so we return to it as it is.

It’s been six years since we started using an outdoor bathroom next to the house, also roofed with zinco. With the first rain this year, part of our living rooms’ ceiling fell down, and the walls in the other room cracked. I reviewed the UNRWA and asked them to send a committee for inspection. They did send a committee to register the damages, but till today, the restoration is yet to happen.

We are not allowed to do renovations on our own. Primarily, construction materials were not allowed inside the camp except through UNRWA. And if we try to recondition, the cost of those materials is so high that we cannot afford it. Other than that, this exposes us to confinement by the army intelligence.

We didn’t have any solution. I left the house with my family, and we rented another one within the camp.

Testimony 4 | Ein el Helwe camp

I have been living with my husband in this house for more than ten years, and its condition was tolerable, compared to other houses in the camp. Seven years ago, during a funeral, a bullet pierced the wall of a room, and another hit the ceiling of the kitchen. With the first winter afterwards, water leakage began, and with it cracks appeared.

We submitted an application for house renovation to the UNRWA in that same year. We were asked to wait and review in a year. The following year, we were informed that our application was rejected, with no explanation of the reasons.

Every year, we resubmit the application, but to no change.

The house might collapse on us. I live with this fear every moment, but we just can’t vacate. We have no relatives that can host us, and we are unable to rent a house. All I have is the hope that they might “have mercy on us”.

Appendix

Activists contacted by “Akhbar Al-Saha” complain that the restoration applications submitted through UNRWA take a long time to be processed, and that there is always nepotism in favour of the armed factions. This discrimination is not only limited to urgent repairs, whose requests are often rejected, but extends to the construction of new houses as well as buildings.

An activist in Bourj al-Shamali camp says that last year “Fatah movement” built a 3-storey building with an official permit, obtained by bribing an army officer, according to camp residents. In the same way, according to him, the factions obtain permissions to repair their own houses, without any care to the civilians’ homes that fall over it’s owner’s heads.